Urho Kaleva was born on 3 September 1900 in Pielavesi in a humble cottage called Lepikko. He was the first child of Juho Kekkonen and Emilia Pylvänäinen. His father was originally a farmhand and forestry worker, but he joined the emerging middle class by becoming a forestry manager and stock agent. His mother was the daughter of an independent farmer. The family moved frequently due to his father’s work, and Urho attended school in Kajaani.

Urho was an unruly boy who nevertheless liked writing. His first writings were published in the local newspaper Kaikuja Kajaanista. At Kajaani Coeducational Secondary School, Kekkonen’s energy and his tendency to rashly transcend the bounds of propriety were becoming apparent. At the age of 17 he joined the Kajaani Civil Guard and fought in the Civil War on the side of the Whites. He took part in fighting and commanded a firing squad that executed nine Reds in Hamina in the spring of 1918. He graduated in 1919 and did his military service with the Helsinki Transport Battalion, where he obtained the rank of sergeant.

Studies

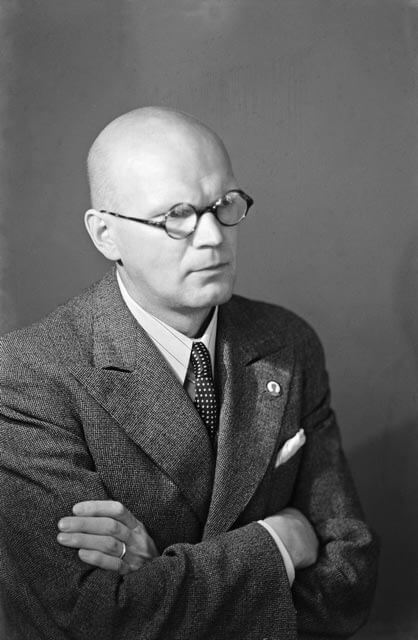

Urho attended the University of Helsinki and swiftly completed his studies, graduating with a Bachelor of Laws degree in 1926. At university he was active in the Northern Ostrobothnian Student Association, where he led an active student life among law students, and he was the editor-in-chief of the student newspaper Ylioppilaslehti. He was also a gifted athlete and became Finnish high-jump champion in 1924. He earned his Master of Laws degree in 1928.

Career

While studying Kekkonen worked for the security police between 1921 and 1927, where he became acquainted with anti-communist policing. During this time he also met his future wife Sylvi Uino, a typist at the police station and the daughter of a pastor from a small town Pieksämäki. They were married in 1926 and had twin sons, Matti and Taneli, two years later. Sylvi Kekkonen later became a writer.

Kekkonen’s doctoral dissertation, completed in 1936, dealt with municipal suffrage under Finnish law. His ideological roots lay in the nationalistic student politics of the newly independent Finland. The unification of the nation, hatred of the Russians, the linguistic struggle on behalf of Finnish, and the Eastern Karelia question were also important to him. He was a member of the Academic Karelia Society, which supported the annexation of East Karelia, and he wrote columns for its journal. He resigned from the organisation after its support the Mäntsälä rebellion in 1932.

Political career

Kekkonen belonged to the first generation of intelligentsia from rural areas. He did not become a party politician until 1933, when he became a member of the Agrarian Party, gained a post in the Ministry of Agriculture and made his first attempt to enter Parliament. Kekkonen visited Germany in 1932 and 1933 in connection with his dissertation, and he witnessed Hitler’s rise to power. Communism had been banned in Finland, and Kekkonen wrote a pamphlet entitled Demokratian itsepuolustus (“The Self-Defence of Democracy”) in which he drew attention to the threat from the extreme right.

Kekkonen was elected to Parliament on his second attempt in 1936. He was appointed the second Minister of the Interior in Kyösti Kallio’s cabinet. As Justice Minister in A. K. Cajander’s Socialist-Agrarian cabinet, his most conspicuous action was an unsuccessful attempt to ban the right-wing extremist Isänmaallinen Kansanliike (Patriotic Popular Movement) in 1938.

Kekkonen was not a member of the cabinets during the Winter War or Continuation War. He opposed the Moscow peace treaty in Parliament in March 1940. During the period of the Second World War he served as director of the Karelian Evacuees’ Welfare Centre from 1940 to 1943 and as the Ministry of Finance’s commissioner for coordination from 1943 to 1945, his task being to rationalise public administration.

His official duties and his membership in Parliament did not satisfy Kekkonen’s thirst for action. In 1942 he began writing reports on foreign and important domestic political issues under the name of Pekka Peitsi for the weekly magazine Suomen Kuvalehti. The turning point in Kekkonen’s thinking came in late autumn 1942, when he began to align himself with the “peace opposition”. Following the Continuation War many of the leading figures in the peace opposition rose to political prominence.

Kekkonen’s views on foreign policy finally coalesced in 1944. The most important consideration was to eliminate Soviet suspicions and thus to create conditions for mutual trust. At its 1945 congress, Kekkonen stated that “the Agrarian Party must further establish an orientation suited to the new world order”. He demanded that “all of our public life should be made to conform with a metamorphosis aimed at the achievement of good mutual understanding”.

Kekkonen made his final breakthrough into the inner circle of politics when he was chosen as Justice Minister in the cabinet of J. K. Paasikivi in November 1944. One of his responsibilities was dealing with war-guilt issues associated with the political trials demanded by the Allied Control Commission. When Paasikivi became President in 1946, the Agrarian Party proposed Kekkonen for the post of Prime Minister, a move thwarted by the opposition of the Finnish People’s Democratic Union (SKDL), the communist front organisation. Kekkonen became a member of the Board of Governors of the Bank of Finland, but his main sphere of political influence was in Parliament, first as Deputy Speaker and then as Speaker. In the presidential election of 1950 Kekkonen was chosen as the candidate for the Agrarian Party and conducted a vigorous campaign against the incumbent president, J. K. Paasikivi. Kekkonen received 62 votes in the electoral college, while Paasikivi was elected with 171. After the election Paasikivi appointed Kekkonen Prime Minister. Four further Kekkonen cabinets followed.

In the latter half of his first cabinet’s term, he began placing ever greater emphasis on the 1948 Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance (YYA Treaty) between Finland and the Soviet Union, which became “the basis of everything”. Kekkonen soon developed relations with the East as his most important political tool, which he used time and time again to ward off attempts both to bring down his cabinets and to oust him from the office of prime minister and later president.

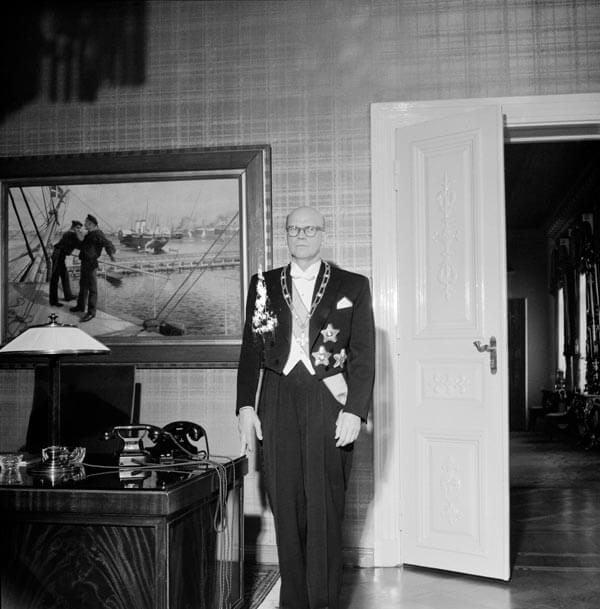

President (25 years)

Kekkonen was elected president in 1956, when he defeated his rival, the Social Democrat K. A. Fagerholm, by two votes. The Central Organisation of Finnish Trade Unions SAK proclaimed a general strike that began on the new president’s inauguration day on 1 March 1956. His presidential term marked the beginning of a new era. By the end of his first year in office, not a single one of his predecessors was still alive.

With Kekkonen’s support, Minister for Foreign Trade Ahti Karjalainen conducted negotiations aimed at fulfilling Finland’s desire to become a de facto member of EFTA in 1961 while at the same time guaranteeing the trade advantages demanded by the Soviet Union. The result strengthened Finland’s Western export markets and its ability to keep pace with integration in Western Europe.

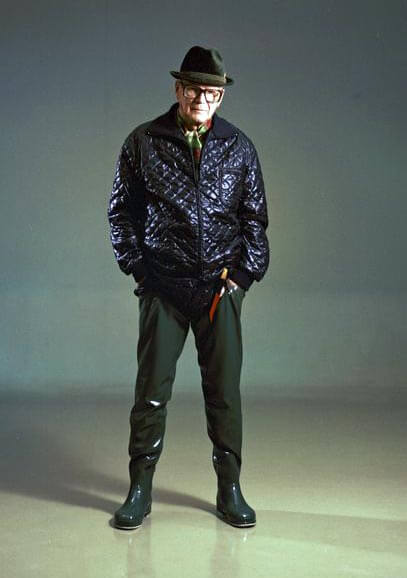

In April 1961 Kekkonen was planning to dissolve Parliament in order to undermine the alliance behind the former Chancellor of Justice Olavi Honka, who had been put forward as a rival candidate in the presidential elections. In addition, the Soviet Union sent a diplomatic note in late October, citing an article of the YYA Treaty referring to the threat of war. Historical research has not arrived at a consensus regarding this “Note Crisis”. The commonly held view is that the Soviet Union was motivated by a desire to ensure Kekkonen’s re-election. As a result of the crisis, genuine opposition to Kekkonen disappeared, and he acquired an especially strong – later even autocratic – status as the political leader of Finland. Together with his supporters he created a personality cult of a virile man of the common people, as an active sportsman who loved to ski, jog and fish, and who knew how to deal with the Soviet leadership in a way that kept Finland a western state.

Under the Finnish system the President cannot exercise power indefinitely without the support of a majority of the parties. In order to ensure such support Kekkonen employed a very complex concept of “reliability” in foreign politics – which meant supporting Kekkonen and his foreign-policy line – as a condition for being allowed to participate in Government. Another tool that Kekkonen employed to wield power consisted of his uniquely comprehensive personal networks: he kept in close contact with former fellow students and his hunting, fishing and skiing mates; he gave “children’s parties” for up-and-coming young intellectuals at his Tamminiemi residence; and he groomed trusted individuals for careers in the different branches of public administration, in the business world and in all the major parties.

He had the ability and energy to mix with the most varied range of people and social circles. He also composed many letters to influence various issues in the direction he wanted. Recipients of these letters knew what was expected of them. As a wielder of power, Kekkonen can be likened to the conductor of a symphony orchestra keeping a personal grip on all the players as he directed his own composition.

In the area of foreign policy Kekkonen acted alone, helped only by assistants whom he himself chose and who came mostly from the Ministry for Foreign Affairs. In the 1960s Kekkonen was responsible for a number of foreign policy initiatives regarding the Nordic nuclear-free zone, the border agreement with Norway and the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE, 1969). The purpose of these initiatives was to avoid the enforcement of the military articles in the YYA Treaty – in other words, military cooperation between Finland and the Soviet Union – and support Finland’s policy of neutrality.

Following the invasion of Czechoslovakia (1968), pressure for neutrality increased. Kekkonen informed the Russians in 1970 that he would not continue as president, nor would the YYA Treaty be extended, if the Soviet Union was no longer prepared to recognise Finland’s neutrality.

The world situation following the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 and the hardening of the Soviet Union’s policies towards Finland worried Kekkonen, who considered himself the only person in Finland capable of withstanding the mounting pressure. As a result, he succeeded in extending his presidency for four years in 1973, without elections, by means of an emergency act. His beloved wife Sylvi passed away in 1974. Even though Kekkonen was known to have several mistresses, he was deeply affected by the loss of his wife.

The Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE) that Kekkonen hosted in Helsinki in 1975 helped strengthen Finland’s neutrality and marked the zenith of Kekkonen’s long political career. Finland and Kekkonen were the centre of the world’s attention during those weeks. Subsequently, however, it became clear that the Soviet Union did not respect Finnish neutrality as it attempted to bind Finland closer to its sphere of influence on the basis of the YYA Treaty. Once again Kekkonen dealt with the situation by threatening to resign during a state visit to the Soviet Union in 1977. The following year he also turned down a proposal by Soviet Defence Minister Dimitri Ustinov to hold joint military exercises.

In terms of domestic politics, the 1978 presidential elections were merely a show. Kekkonen’s health began to fail, and he grew weak and suffered occasional memory lapses. Nevertheless, he was still considering a fifth term. The de facto end of Kekkonen’s career as an autocrat came in April 1981, when Prime Minister Mauno Koivisto refused to resign, although suggestions to this effect had been heard coming from the presidential residence at Tamminiemi. Koivisto broke the pattern of the Kekkonen era by appealing to the notion that in Finland a government should first and foremost enjoy the confidence of the Parliament and not of the President.

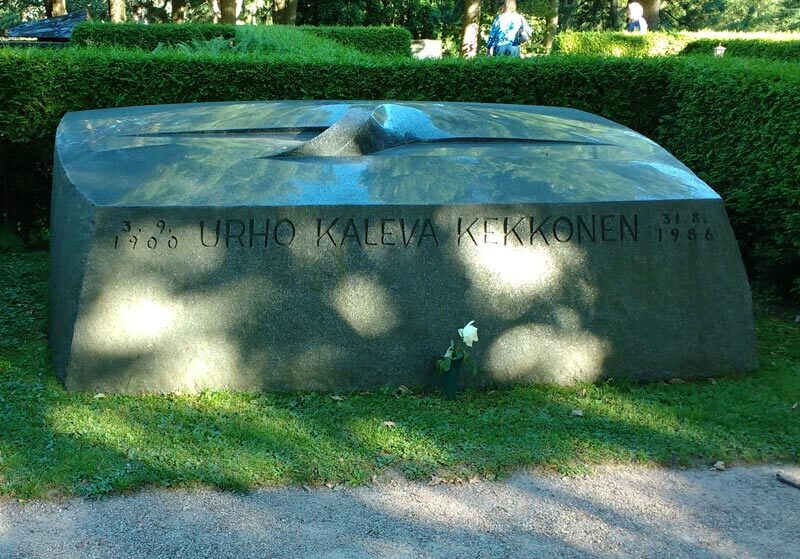

Kekkonen’s health let him down visibly for the first time during a fishing trip in Iceland in August 1981. In September he went on sick leave, and in October he submitted his resignation, after which he did not appear again in public. Kekkonen remained a sick man at Tamminiemi until his death in 1986.

Urho Kaleva Kekkonen is buried in Hietaniemi Cemetery in Helsinki. Tamminiemi now serves as a museum.