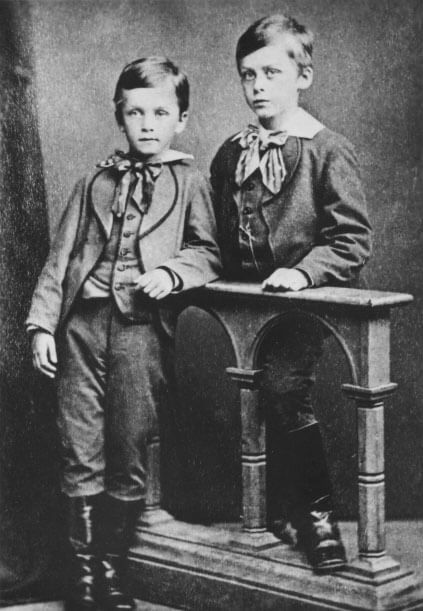

Gustaf was born on 4 June 1867 at Louhisaari Manor in Askainen, South–West Finland. As the third of seven children of a noble family, Mannerheim inherited the title of Baron, only the eldest son would inherit the title of Count. His father, Count Carl Robert Mannerheim, was an industrialist and businessman. Unfavourable economic trends, gambling and socialising forced him into bankruptcy and the family was forced to sell their manor house. Father deserted his wife and children, travelling instead to France and the USA. Under the strain as a single parent, mother Hélène von Julin died of a heart attack at the age of just 38, when Gustaf was only 14. Gustaf’s childhood was marked by the bankruptcy of his father, the disintegration up of his family and the premature death of his mother. The children were split up to be raised by relatives. Gustaf himself was raised primarily by his maternal uncle, Albert von Julin.

Military career

The stubborn and ambitious boy was enrolled at the age of 15 at the Hamina Military College in 1882, but he was expelled for breach of discipline. He continued his studies at a private grammar school in Helsinki and passed his university entrance examinations in 1887. A military career opened up for him again when he was admitted into the Nikolayev Cavalry School in St. Petersburg in September 1887. The demanding military school suited Mannerheim. Following representations made to the Empress Maria Feodorovna by female relatives of social standing and the financial support of an uncle, he was appointed to H. M. the Empress’s Chevalier Guard. This cavalry regiment formed part of the Imperial Life Guards. By 1893 Mannerheim had been promoted to lieutenant of the guard.

Mannerheim was a handsome, well-groomed and upright soldier with a serious demeanour that was offset by his social graces. He was eventually freed from his constant financial worries in 1892 when his relatives arranged his marriage to Anastasia Arapova, the daughter of a well-to-do general. The couple had two daughters, Anastasie and Sophie. The marriage did not last, however, and the two were divorced after ten years of marriage. Anastasie and the children moved to live in Paris.

In order to advance his career, Mannerheim volunteered for the front when war broke out with Japan in 1904. He earned the respect of his superiors and was promoted to the rank of colonel in recognition of his valour. Around this time Mannerheim began planning a major expedition across Asia. He was inspired by the great explorers of his age, including his relative Nordenskiöld.

On returning from the Japanese War, Mannerheim attended the last session of the Finnish Estates as a representative of the baronial branch of his family. Then he formed personal ties with the Finnish political elite. He continued preparations for his military-scientific Asian expedition and forged important links with academic and culturally nationalist Fennoman circles.

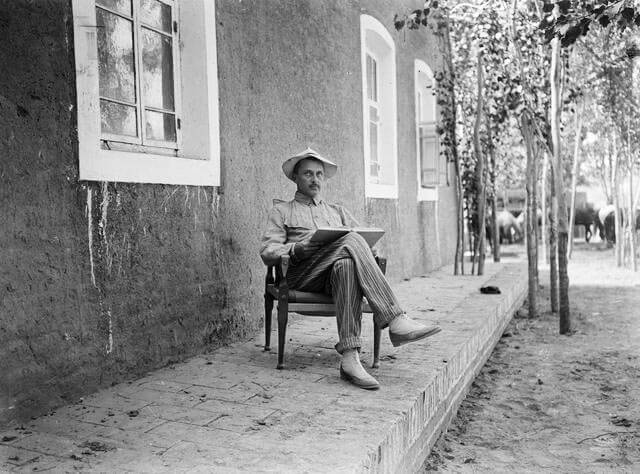

Mannerheim began his long expedition across Asia on horseback in Turkmenistan in October 1906. Accompanied by only a couple of men, he rode through areas belonging almost entirely to China. His military task was to investigate the mostly uninhabited mountain and desert regions that were of interest to Russia, China and Great Britain. He also collected ethnographic material that showed considerable scientific talent and ambition.

Mannerheim returned to St. Petersburg in September 1908. At the beginning of 1909 he finally became commander of a Guard regiment, albeit in Poland. In 1911 he transferred to Warsaw as commander of H. M. the Emperor’s Guard Regiment of Uhlans. There Mannerheim spent one of the happiest periods of his life, and he became deeply attached to Princess Marie Lubomirska.

During the World War that broke out in 1914 Mannerheim served as a front-line commander, mostly on the fronts with Austria-Hungary and in Rumania. On 18 December 1914 Mannerheim was awarded the St. George Cross for valour.

Following the October Revolution in 1917 in Russia, the newly independent Republic of Finland found work for Mannerheim, who had been relieved of his duties in the Russian Army in September. The Finnish Senate began disarming Russian garrisons on Finnish territory and expelling them from the country. Troops formed on the basis of the Civil Guards were used for the task. In January 1918 the bourgeois Senate headed by P. E. Svinhufvud appointed Mannerheim commander-in-chief of the pro-government Civil Guards. The Jaegers, Finnish volunteers who had received military training in Germany and fought on the Eastern Front against Russia, provided much-needed military expertise to the White forces. What began as a war of liberation, however, became a bitter civil war following an anti-Government uprising by the Reds. They were supported by the Bolsheviks. The resulting war between the Whites and Red lasted throughout the first five months of 1918. With the help of German forces, which liberated Helsinki, the Whites emerged victorious.

In order to emphasise the Finnish, non-German nature of the war of liberation, Mannerheim organised a great victory parade of his army in Helsinki on 16 May 1918. The Red government in Helsinki and its forces there had been crushed a month earlier by General Graf von der Goltz and his troops and pro-German feeling was strong in the city.

Mannerheim was opposed to the Senate’s pro-German political and military orientation. It was moving Finland entirely into the German sphere of influence in order to gain security against Russia and Finland’s own Reds. When the Senate refused to agree to Mannerheim’s demands, he left the country on 1 June 1918, convinced that France and Great Britain would eventually win the war.

Mannerheim was thus out of the country during the last, fateful period of the Civil War, a time of mass deaths as a result of disease and starvation in the large prison camps and of lengthy trials. During the war he had already tried to stop the “White terror” and had opposed the mass imprisonment of Reds and the legalistic, case-by-case way in which they were tried for treason.

The collapse of imperial Germany necessitated a change of government in Finland. In autumn 1918 Mannerheim held discussions in London and Paris, securing large shipments of food from the Western powers that saved Finland from mass starvation. On 12 December 1918 Mannerheim was invited to assume supreme power temporarily after Svinhufvud with the title of Regent. This was until the question of a form of government was resolved. In the spring of 1919 he succeeded in gaining recognition of Finland’s independence by Great Britain and the United States and the renewal by France of the recognition that it had already agreed to grant but had subsequently withdrawn.

Mannerheim used this recognition and his state visits to Stockholm and Copenhagen, as well as other symbolically important acts, to fundamentally consolidate Finland’s new sovereign status, attempting to bind the country to the victor states of France and Britain, as well as to Sweden.

Under the provisions of Finland’s new constitution, a President of the Republic was elected for the first time on 25 July 1919, with votes cast by Parliament. Mannerheim received 50 votes from members of the Conservative National Coalition Party and the Swedish National Party; but the President of the Supreme Administrative Court, K. J. Ståhlberg – the candidate of the Agrarian Party, the Progressive Party and the Social Democrats – won 143 votes and was elected.

Mannerheim subsequently withdrew from politics for the next twelve years. The Finnish nation remained divided, and right-wing radicalism came to the fore with the so called Lapua Movement. In March 1931, soon after coming to power as president as a result of the period of agitation, president P. E. Svinhufvud appointed Mannerheim Chairman of the Defence Council and Commander-in-Chief in the event of war, thus formally reintegrating him into the governmental system. In 1933 Mannerheim was given the rank of Field Marshal.

Commander-in-Chief 1939–1944

Despite constant pressure from Mannerheim, large sections of the army were poorly equipped in the autumn of 1939. During the Finnish-Soviet border and security negotiations, Mannerheim felt that Finland did not have the wherewithal to pursue such a tough line as that taken by the government. He recommended agreement to territorial concessions and exchanges, several times, threatening to resign. After these negotiations bogged down, war broke out on 30 November 1939. Mannerheim assumed the position of Commander-in-Chief and established his headquarters in Mikkeli, where he spent most of his time as Commander-in-Chief until 31 December 1944. Despite his age and health problems, he worked incessantly throughout the war with only a few very short leave periods. He sat an example to his headquarters and to the entire army and nation of the commitment demanded by the situation.

During the Winter War of 1939-40, the ensuing interim peace and the Continuation War that began on 26 June 1941, Mannerheim was a member of the group of four or five people that constituted the country’s de facto leadership. In addition to Mannerheim, this circle included Risto Ryti, who became president in 1940, prime ministers J. W. Rangell and Edwin Linkomies, foreign ministers Väinö Tanner, Rolf Witting and Henrik Ramsay, and General of the Infantry Rudolf Walden, who served as Minister of Defence throughout this period. Mannerheim exercised an important influence on the conduct of the Winter War and attempts to achieve peace. He pointed out that, despite its heroic defensive victories, the army was weak. Its endurance was stretched to the limit. Therefore, even the toughest peace terms had to be accepted – as in fact happened.

The conclusion of the Winter War was followed by constant pressure from the Soviet Union, due to the prevailing global situation. The only possible counterweight was Germany, which was initially in alliance with the Soviet Union. From September 1940 onwards, however, Germany gradually began to take Finland under its protection with regard to the Soviet Union. From the beginning of 1941 military contacts between the headquarters of the two countries gradually strengthened, though right up to the last moment it was uncertain whether Germany would launch a war against the Soviet Union.

During this period Finland was able to significantly improve the preparedness of its army. An important part of the Marshal’s conduct of the war from 1941 to 1944 was the psychological aspect. He maintained his authority over his generals at headquarters and the commanders on the front. As the conflict dragged on he reduced the quarrelling and competition characteristic of wartime. The political importance of such authority was also evident in the relationship with Germany: of all the Finnish leaders, Mannerheim made the clearest demands concerning formal and actual respect for Finland’s political and military independence. That was made evident on Mannerheim’s 75th birthday on 4 June 1942, when Germany’s Führer Adolf Hitler arrived to offer his personal congratulations to Mannerheim, who had just been appointed Marshal of Finland.

Mannerheim’s behaviour on this occasion has been described as an exemplary combination of extending courtesy while at the same time keeping a firm grasp on one’s own authority. This enabled Finland to reject Germany’s demands for ultimate authority or for a formal treaty of alliance. Finland was able to get away from the Germans with the personal guarantee offered by President Ryti to Germany´s foreign minister Ribbentrop in summer 1944. Ryti guaranteed personally, that Finland would not make peace with the Sovjet Unioin without the approval of Germany. This guarantee was valid for only a few weeks before Ryti was replaced.

President

The Soviet offensive of June–July 1944 forced the Finnish army to retreat in Karelia and to withdraw to the west of Vyborg on the Karelian Isthmus. This led to a readiness to agree the harsh peace terms. A precondition for peace was a change of government and the severing of ties with Germany. Mannerheim consented to this, and on 4 August 1944 he was elected President of the Republic by the Parliament.

Thus began the peace process, the timing of which Mannerheim clearly achieved in the best possible way. Germany was already considered too weak to squander its energy on occupying Finland. For its part, the Soviet Union was no longer interested in a total surrender or the military conquest of Finland. It was now concentrating its energies on the Baltic states, Poland and Germany. The Western powers and Sweden were prepared to give political and also economic support for a separate peace for Finland. Also, after the loss of Eastern Karelia, the Isthmus and Vyborg, the Finnish public was prepared to accept harsh peace terms.

Mannerheim directed the peace negotiations, with the firm support of the Finnish Ambassador to Sweden G. A. Gripenberg, simultaneously as president, commander-in-chief and in practice also as prime minister and foreign minister, especially after Prime Minister Antti Hackzell was paralysed in the midst of the process. His authority was of crucial importance in dealing with the moods of the nation and especially in managing the army. The army had to be reoriented swiftly and in the most concrete fashion. Relations with Germany and its forces in northern Finland were broken off. Corresponding ties had to be created with soldiers – and soon civilian representatives – of the former enemy, the Soviet Union.

Mannerheim’s authority was of great importance when the Allied Control Commission was installed in Helsinki after the interim peace settlement. A new government of politicians formed by J. K. Paasikivi replaced short-lived presidential caretaker governments in November 1944. At this point the concentration of powers that Mannerheim had held during the peace process came to an end, and despite grave misgivings, he also finally accepted a communist – Interior Minister Yrjö Leino – as a member of the new Paasikivi government.

By this time Mannerheim’s health was failing. He travelled to Stockholm for an operation and later to Portugal for a holiday, diminishing his role in the leadership of the country. Although Mannerheim had been elected president for an emergency period, he did not wish to resign immediately after the parliamentary elections of spring 1945. The international situation was still unclear, with the war in Europe continuing until May 1945. Mannerheim feared that he would be convicted in the war-guilt trials provided for by the interim peace treaty and now being pressed forward by the Allied Control Commission.

It was in the interests of both the Finns and the Soviet Union, however, to spare Mannerheim from such a fate. After this matter had been cleared up, he resigned in March 1946. University students showed their respect with a torchlight procession – an important gesture considering the times. The communists, too, were prepared to recognise Mannerheim’s significant role in the achievement of peace.

Thereafter Mannerheim devoted himself to attending to his failing health and writing his memoirs, mainly at the Valmont sanatorium in Montreux, Switzerland. When Mannerheim passed away on 27 January 1951 (28 January Finnish time), his memoirs were so close to completion that it was possible to publish the first volume in the same year.

Mannerheim is buried in Hietaniemi Cemetery in Helsinki.

The longest street in the Helsinki city center is named after Mannerheim.