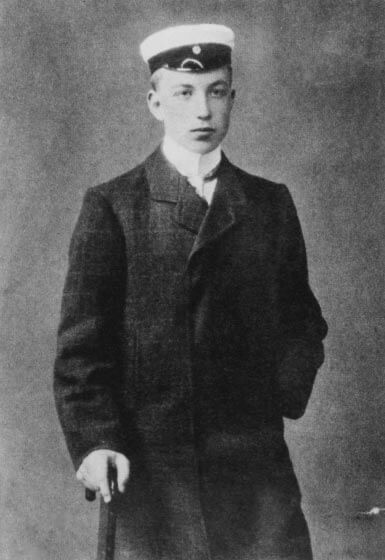

Risto Heikki Ryti was born on 3 February 1889 in the village of Huittinen, Satakunta. He was the fourth of 11 children. His father Kaarle Evert Ryti was a farmer with over 200 hectares of cultivated land and 50 head of cattle, while his mother Ida Vivika was the daughter of a farmer. Both parents were enlightened and ambitious. In terms of politics, the family supported the Young Finns. The family’s sons were active in politics in the first half of the century. Risto had a weak constitution, a sallow complexion and a greater interest in reading than in farm work. Of the eight sons, he was the only one to pass the university entrance examinations, as did his three sisters. By nature Risto was determined, conscientious and ambitious. He had a rational approach and did not let his feelings get in the way.

Risto dealt with his studies quickly and only attended traditional primary school for a brief period before the director of an adult education institute, M. A. Knaapinen, was engaged as his home tutor. Risto graduated from upper secondary school in Pori in 1906 at the age of 17 and enrolled in the same year at the Imperial Alexander University, today known as the University of Helsinki. He graduated with a degree in law in 1909.

Career

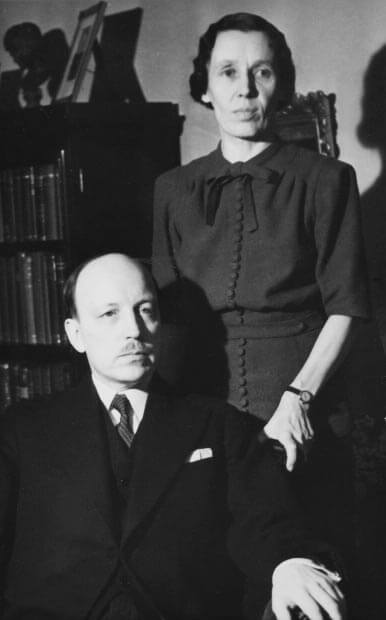

With the onset of the second period of Russification in Finland, Ryti decided to leave the capital and become a lawyer in Rauma, a lively trading and shipping town. During this period he became acquainted with Alfred Kordelin, who was known as the “richest man in Finland”. Ryti became Kordelin’s lawyer, and the two established a close friendship. Ryti also undertook further studies and received his Licentiate in Law in 1912. He got to serve in the District Court and continued his education, earning his Master of Laws degree in 1914. In the same year he travelled to Oxford with his friend Eric Serlachius to study maritime law, but his studies were cut short by the outbreak of the First World War. Ryti fell in love with Eric’s sister Gerda Serlachius, who had been hired to work in the law office of Ryti and Serlachius. Risto and Gerda married in 1916 and enjoyed a warm and enduring marriage. They had three children: two sons and a daughter. Surrounded by his family, Ryti revealed a humorous and playful side to his character.

Risto Ryti and his wife Gerda were guests of Alfred Kordelin at Mommila Manor celebrating the host’s 49th birthday on 6 November 1917 when Russian sailors, carried away by the Bolshevik Revolution that had broken out in Russia, attacked. The Russians took Kordelin and his 20 guests prisoner. The following morning they took the prisoners to the railway station with the intention of taking them to Helsinki. On the way, however, a skirmish broke out between the Russians and Civil Guards, who had been called to help. In the chaos that ensued, one of the sailors shot Kordelin. Risto and Gerda Ryti escaped into the nearby forest. Risto Ryti executed Kordelin’s will, setting up the Alfred Kordelin General Progress and Education Fund, the first major national and Finnish-language culture fund in Finland.

Political career

Risto Ryti was the most promising young talent in both economics and politics in the young republic. He was elected to Parliament in 1919 as a representative of the National Progressive Party at the age of 30. Over the next three years he served twice as Minister of Finance, in which position he succeeded in bringing order to budget estimates. Although he was a political ally of President Ståhlberg, he opposed his spiritual father on one important issue: he did not approve of the pardoning of Red prisoners. In Ryti’s opinion the Reds were criminals, and he refused to see the events of 1918 within the social context.

President Ståhlberg appointed Ryti Chairman of the Board (Governor) of the Bank of Finland at the age of just 33. The work he did in this position proved to be of inestimable value to the Finnish economy.

Prime Minister

Throughout the 1930s, as Governor of the Bank of Finland, Ryti had been in a certain sense a political reservist, ready to assume responsibility for the nation’s interests if required. In late autumn 1939, with the Winter War looming, the nation required a cool and rational leader. Even though Ryti initially tried to turn down the post of prime minister when it was offered to him, President Kallio appealed to Ryti’s sense of responsibility and put pressure on him to accept the position. Battered but alive, Finland survived the unequal struggle of the Winter War. It can be regarded as an act of statesmanship on the part of Ryti that the Moscow Peace Treaty was signed on 13 March 1940. By signing the treaty, Ryti became a prime minister of peace in the eyes of the Russians and thus an acceptable figure for the post of president.

President

Risto Ryti had proven to be a strong prime minister. President Kallio was ill and also had no great experience in foreign policy, which was handled mainly by Prime Minister Ryti and Foreign Minister Väinö Tanner. In December 1940 Kyösti Kallio resigned as president due to illness. At the age of 51, Risto Ryti’s first task as president was to inform the nation of Kallio’s death on 19 December 1940.

President Kallio had made Gustaf Mannerheim commander-in-chief of the defence forces at the start of the Winter War. According to the constitution, Mannerheim should have handed back command to President Kallio when the Moscow Peace Treaty came into force. However, Kallio wanted Mannerheim to continue in this capacity, because the general situation was difficult and a world war was still raging. Ryti had nothing against this arrangement, as a result of which he is the only Finnish president who did not act for a single day as commander-in-chief of the armed forces.

Ryti had been elected as president on 19 December 1940 only for the remaining period of Kallio’s term, i.e. until 1943. In a situation of war, however, elections for a new electoral college were unthinkable, and thus the members of the 1937 electoral college convened to vote in February 1943. This time too Ryti was elected by an overwhelming majority, and he had to serve as president during the toughest period in our nation’s history, the Continuation War.

The Soviet Union launched a massive counter-offensive against Finland in summer 1944 with the aim of achieving a rapid resolution. Finland was in desperate need of weapons and support, and they were only available from Germany. In June 1944 Ryti sent a letter to the German foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, requesting military assistance. Ryti signed the letter in his own name, knowing with his legal background that only he personally would be held accountable. The letter represented a personal commitment to avoid reaching a separate peace with the Soviet Union without Germany’s approval. When signing the letter, Ryti remarked that, “By signing this agreement I am preventing a military catastrophe and the occupation of our country, which would result in a terrible disaster for our nation.”

Ryti was hospitalised for two weeks after signing the agreement and resigned as president in part for health reasons. When the military situation had stabilised by mid-July following defensive victories by Finland, procedures for a change of president began. By a special law, Parliament appointed Mannerheim president in early August 1944, and the agreement that Ryti had signed became obsolete.

In spring 1945 foreign-policy pressures and the demands of the communists in Finland led to the arrest and trial of Ryti and others to face charges of “war guilt”. On 21 February 1946, after considerable pressure from the Soviet Union, Ryti Ryti was sentenced to 10 years imprisonments. He ultimately sat for three years in Sörnäinen Prison in Helsinki. He was pardoned by President Paasikivi in May 1949, but his health had collapsed. Ryti died on 25 October 1956 at the age of 67. Ryti’s funeral in November turned into an ardent, patriotic ceremony of mourning at which his life’s work was granted great recognition.

Risto Ryti is buried in Hietaniemi Cemetery in Helsinki.